Subjects under post-Fordism and neoliberalism must be able tolerate precarity without breaking down so much that they can't work efficiently. They must be comfortable shifting from steady wage work to a series of projects secured through whatever means necessary and be more or less self-motivated. Consumerism helps model this, putting a positive spin on the demands for flexibility and opportunism, positing these qualities as the embrace of novelty and perpetual self-reinvention. Consumerism promises that magical transformations are easy, available on demand, and that a self understood in terms of lifestyles and personality experiments—rather than in terms of communal tradition, meaningful work, or the continuity of life experience—can be a worthy expression of individual freedom.

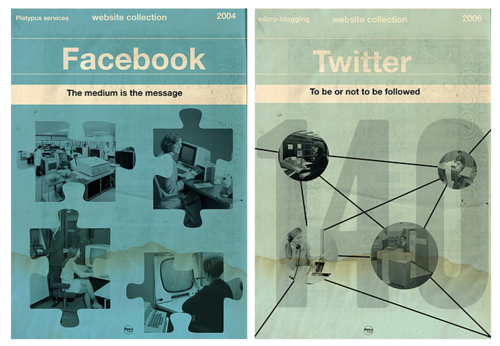

Social media—Facebook and other similar services that have integrated with portable devices to permit continuous interactivity—have furthered consumerism’s ameliorating mission. They enhance the compensations of consumerism by making it seem more self-revelatory, less passively conformist, conserving the signifying power of our lifestyle gestures by broadcasting them to a larger audience and making them seem less ephemeral. They temper the anonymity and anomie that consumerism’s mass markets tend to impose by concretely attaching our identity to what we consume. They also provide new mechanisms of solace, administering doses of proof of our connectedness and influence. (As in: Oh, look! I’ve been retweeted!)

Because of the way they are structured, social media urge us to continually devise ingenious new solutions to our identity, which is suddenly cast in sharp relief as a particular kind of recurring problem, one that needs solving by replenishing social media’s various channels with fresh content. Our presence in social media doesn’t reflect some pre-existing self; it depends on our deploying signifiers of the self, recontextualizing them and promoting them as attention-worthy. This prompts us to develop what Paolo Virno called "communicative competence" and habits of voluntary collaboration in elaborating cultural meanings—this can be seen in the programmatic interactions Facebook orchestrates around the various cultural materials it encourages users to supply.

Euphemistically described as “sharing,” this sort of work is that which advertisers have traditionally performed in consumer societies—generating or augmenting affective meanings for goods and allowing those meanings to float free. Social media seek to corner the market on the expression of individualism. Facebook wants to be the place where you feel most yourself, with the most control over how you are regarded. The online repository becomes a privileged site of the self, the authorized version that redeems the provisionality of work life and that can correct the errors and discourtesies we commit in our confrontations with the everyday in the physical world. But in return, it wants you think of yourself only in terms of what you can share on the site, what can feed its databases. It implements freedom of self-representative choices as a mode of control; our identities are "unfinished" but contained by the site, which ensures that more of our social energy is invested in self-presentation there—selling objectified fragments of ourselves as though we are consumer goods.

Through social media, a fashion-like imperative of constant, superficial self-reinvention begins to govern more and more of social life under the guise of facilitating connection and permitting ongoing self-discovery. Our Facebook updates don’t allow us to express ourselves so much as allow consumerism to express itself through us while we provide the labor that sustains it as a communication system. We are produced within that system, with an identity that is expressed through what Baudrillard labeled the “code”—consumerism’s systemized set of signifiers. On social media, we leverage the code to enhance how we are perceived, thus replenishing that code for further cycles.

Social media archives these identity-making gestures as a collection we can continually fawn over and curate. The archiving makes the self seem richer and more substantial even as it makes it more tenuous. Our identity can never be so strong as to render any particular recorded gesture completely negligible; the self becomes cumulative at the same time as it is discontinuous. This has the effect of making whatever is shared through social media seem deeply significant to who we are and unsettlingly irrelevant at the same time.

In social media, advertising’s perennial message—that one’s inner truth can be expressed through the manipulation of well-worked surfaces—becomes practical rather than insulting. We no longer need to fear "selling out" by blending self-expression with hype, as the terms of service of online selfhood already presume our sell out as a foregone conclusion. We sell out simply by choosing to have subjectivity on social media’s terms. Selling out becomes the prerequisite for achieving an even more authentic-seeming self, one that is routinely validated by peer recognition and by recommendation engines, predictive search, and other automatic modes of anticipation.

Through social media, our consumerist satisfactions are captured and fed back into the production cycle as a component of the manufacturing process, regulating supply and furnishing innovation ideas. Maurizio Lazzarato described this sort of productive communication as immaterial labor, work that “seeks to involve the worker’s personality and subjectivity within the production of value.” This is labor that “produce[s] the informational and cultural content of the commodity." He associates this labor generally with "audiovisual production, advertising, fashion, the production of software, photography, cultural activities, etc."—jobs once typically associated with the “metropolitan" creative class, whose suitability for this sort of work came not from mastering specific skills so much as from having an appropriate taste-making habitus.

But this group’s apparent monopoly on social creativity, if it ever existed, serves only to structure immaterial labor itself as glamorous, as being somehow its own reward. The capacity to perform creative labor is naturally inherent to sociality, a fact on which social media has capitalized. Being able to build a personal identity is labor we all can perform. Everyone can express themselves—even if it's just by clicking a thumb's-up next to a status update. In social media, everyone can "share" their off-the-cuff thoughts and moods and secretly dream of their universal relevance, their impact.

Through immaterial labor, one’s entire being and sensibility, including one’s ability to find suitable collaborators, is enlisted in innovating and circulating cultural meanings, Rather than suspend the sense of self in the midst of work, as Fordist labor discipline demanded, immaterial laborers indulge and develop it. If, as Virno claims, post-Fordism’s great breakthrough is in how it “placed language in the workplace” and made linguistic ingenuity exploitable, it also means that work is no longer contained to the workplace or to working hours but instead takes place anywhere we happen on something to share. "Labor and non-labor,” Virno writes, “develop an identical form of productivity, based on the exercise of generic human faculties: language, memory, sociability, ethical and aesthetic inclinations, the capacity for abstraction and learning." In other words, communication, consumption, and sociality serve simultaneously as work and nonwork, while substituting freely for one another. Social media supply the infrastructure for this free exchange.

For the companies that administer social media, the diffuse data supplied through sharing become the substance of, to use Virno’s phrase, “the commerce of potential as potential”—selling not necessarily the content we supply but access to what we are capable of supplying, which embraces the entirety of our social being. These companies need not commit to any particular branding message of their own; instead, they aspire to a welcoming neutrality that intimidates no one. They market giving uncompensated content production for their networks as the fun of participation. Subjects have an investment to make that work pay off, not in wages but in attention. This incentive permits social-media companies, whose market valuations are skyrocketing, to internalize more and more of experience and subject it to capitalism’s interpretive lens. More human behavior is understood in terms of maximization. Other incentives are suppressed.

Social media, besides serving as an omnipresent factory and distribution center for immaterial labor, also supplies a scoreboard by which we can track our performance in the attention economy—number of Twitter followers, number of comments on a recent Facebook update, number of reblogs on a Tumblr post, et cetera. Because there are so many options, we can cycle through them in search of micro-validation.

In accordance with the tenets of the gamification of everyday life, the scorekeeping stokes our will to participate, making sociality competitive and thus more efficient. One scores points by devising new ways to gain attention and by enhancing the value of various other branded goods (including one's friends, who in social media have become brands themselves). We are goaded into devising new ways to deploy our identity in social media, adopting the expedient model of broadcasting ourselves for our audience to consume at its convenience. We regard the ocean of affirmations prompted by social media as mere currency rather than emotional sustenance.

The pursuit of reputational capital, measured in connections, clicks, affirmations, and other actions captured online, sustains users’ productive curiosity in the face of a surfeit of potentially meaningless, futile choices. With each choice tallied, accelerated consumption seems extra efficient rather than corrosive to identity. Since sharing is a processing mode that feels like mastery, users are encouraged to shed any vestiges of market anonymity for full-blown self-revelation, which social networks return to us as affirmation and affect, confirming our capability to produce cool.

The online self thereby seems an opening rather than a precluding of possibilities. Having our communicative “virtuosity” exploited seems like authentication of the self’s social value. Commercial surveillance registers as an undeniable form of social recognition, even if it appears as well-tailored shopping recommendations or relevant advertising. We are rescued from impersonal market relations and have our "unique identity" reinforced by the specificity of our place in social media’s grid and their capability of cannily catering to our singular niche.

Viewed optimistically, social media could be heralded as opening up the possibility that everyone can realize their full potential through consumer creativity that doubles as socially necessary labor. But at the same time, consumers are put under intense emotional pressure to constantly rearticulate themselves in order to simply register as present, negating the enjoyment consumption could provide. Gestures of identity in social media expire almost as soon as they are instantiated. Updates and tweets hit the pool, have their ripples, and then vanish.

By relentlessly increasing the pace of obsolescence, social media prompt us to improvise more and more desperately; they cultivate a panic that we are being left out, left behind, that the zeitgeist of the instant will pass without our participating in it and claiming our share. We have more capability to share ourselves, our thoughts and interests and discoveries and memories, than ever before, yet sharing is in danger of becoming nothing more than an alibi that hides how voracious our appetite for novelty has become. It starts to be harder for our friends and ourselves to figure out what really matters to us and what stems merely from the need to keep broadcasting the self. And so we vacillate between anxious self-branding and the self-negating practice of seeking some higher authenticity: We have to watch ourselves become ourselves in order to be ourselves, over and over again.

Such self-awareness is how the intellectual surplus of immaterial labor becomes a sort of accursed share, leftover from the competitive workplace-brainstorming sessions, the status-hierarchy battles, the arguments over what music and which movies are great, the experience of checking Facebook and feeling outclassed by what your friends have shared, the endless cycles of self-recrimination and self-revision. These are quintessential aspects of the contemporary experience of precarity, an inescapable sense of inadequacy joined with the amorphous threat of social exclusion. So it is that social media’s network effects are stacked against us; without them we would feel more excluded than ever.

We need a sympathetic community within which to realize our individuality, but social media tend to turn efforts to preserve that community into the pursuit of fame rather than recognition. And when we pursue fame, our behavior devolves into familiar forms of self-commodifycation. We replace the pleasures of self-forgetting and immersion in the moment with schemes for the measurable notoriety we imagine we’ll reap. Social-media companies thus don’t facilitate community, despite what they promise. They cater to the fantasy of being a celebrity, the impossible dream of a mass audience for everyone. But to really dissolve the creative class into a universal creativity, the tyranny of “cool”—fashion as a mass-market business; trend spotting as an entrepreneurial vocation; friendship as a quantitative measure; influence as an end in itself—would have to be abolished, not generalized as it is in social media.

With the vast expansion of the capability to exchange our identity as a sign in social media—to valorize ourselves at the same time as we augment the meaning of commercial goods—we reach the apotheosis of individualism, the IPO of the self. Identity becomes a capital stock that we are compelled to expand. When identity serves explicitly as capital to be risked in attention-seeking ventures of cool-hunting as opposed to something that can exceed the dynamics of the market, we can be aware of ourselves only insofar as we see ourselves profiting or not. We start to nourish the self’s equity through entrepreneurial cleverness—how can I get my personal brand out there better, position it properly, and make the right alliances to strengthen the core message I am trying to convey? Thus social media yield a subjectivity well-adapted to neoliberalism, one which applies economic rationality to all social relations and embraces unbounded flexibility.

The neoliberal self as personal brand first appeared in business self-help literature. In 1997, management guru Tom Peters wrote the definitive treatise on it for the business magazine Fast Company, “The Brand Called You,” which advises: “You’re not a worker…You are not defined by your job title, and you’re not confined by your job description. Starting today you are a brand.” This is essentially a recasting of Lazzarato’s immaterial labor, work that exceeds the explicit expectations of bosses. Self-branding, Peters claims, is “inescapable,” so he encourages us to ask ourselves, “What have I accomplished that I can unabashedly brag about?” and “What do I do that I am most proud of?” and then promptly put these up for sale. He admonishes that we must be eternally vigilant about our personal-brand strategy: “When you are promoting brand You, everything you do—and everything you choose not to do—communicates the value and character of the brand. Everything from the way you handle phone conversations to the email messages you send to the way you conduct business in a meeting is part of the larger message you're sending about your brand.” This is more or less the assiduous performativity Virno labeled as “virtuosity,” which has been generalized through social media beyond the precarious workplace to social life as a whole.

Even a decade ago, the bald self-promotion one typically encounters on Twitter and Facebook would have been in questionable taste, and the idea of explicitly leveraging one’s network of friends in order to maximize one’s notoriety would have seemed preposterously alienating. Widespread ambivalence about the effects of social media on intimacy suggests that the alienation is real, as a surfeit of weak ties suffocates stronger bonds, yet stronger bonds seem available only through the online tools that have diminished them. The receptive, supportive community that recognizes you for who you are mingles uncomfortably alongside the advertisers that hope to persuade you to be something more, that are eager to hijack the self you share and make it a partner brand to help sell product. In social media, the reciprocity of friendship becomes indistinguishable from brand synergies; building trust is just another self-aggrandizing solo project in disguise.

Social media, which frankly invites us, as Peters did, to “unabashedly brag” about ourselves and take pride in even the most mundane of our accomplishments (“I just became mayor of Whole Foods on Foursquare!”), extends the implications of the personal brand and empties the self of its capacity for spontaneity, rendering it pragmatically flexible instead. The personal brand seems to afford a calculus by which we can confront and control the risk we face in identity formation, with social media as the feedback mechanism for cost-benefit analyses.

But personal brands also represent the total breakdown of the possibility of collective identity. The structure of social media encourages us to reject that possibility in favor of a pseudo-autonomy of self-creation contained entirely by commercial networks and fully subsumed by capital. The personal brand grows itself on a balance sheet, and it is not limited by any particular context. Like capital itself, it is theoretically infinite and can be represented as preferable to intersubjectivity, which is seen as constraining, an inconvenient evil.

Thus the transformational potential of the enhanced social cooperation on which the economy increasingly depends is neutralized, frittered away in ostentatious narcissism. The self-interested acquisitiveness and insatiability that capitalism encourages remain posited as natural conditions, as inescapable human nature. Our collaborative nature is expropriated, and we ourselves regard it as weakness unless we can turn it to account and make it personally advantageous. We will come to know ourselves in the same way we breathe life into brands through what marketers call "co-creation." We will ourselves be co-created.